An ounce of information

Article by Pnut King

Published on 03/17/2023 in Peanut Market News

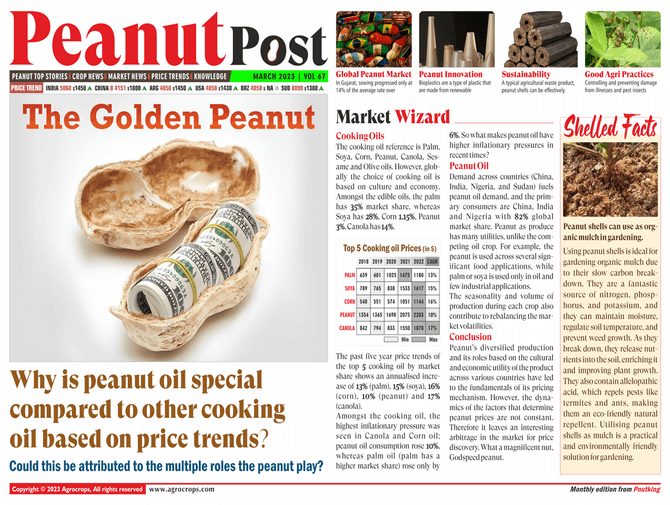

The global peanut trade has developed over many decades. Here’s how we got where we are today, and where we might be going tomorrow.

Doesn’t it feel like peanuts have been around forever? They’re such a significant part of many modern diets, featuring in thousands of snack products, butters, spreads, cakes, and bakes, and now also in the form of oil, flour, and meal.

The market we’ve come to know has a clear structure, with major high-value consumption in the US, Europe, and China, and production centred in South America, India, Nigeria, the US and China.

The trade routes that feed our peanut habit run deep, but like with any global industry, these have developed piece by piece over many years. Influenced by governance, policy, geopolitics, and convenience, these complex networks now support a vast worldwide ecosystem.

In this article, we’re going to explore how these trade routes developed historically, take a look at the biggest influencers that shape our networks, and reflect on what this might tell us about the future of our favourite nut.

From humble beginnings

Peanuts originated naturally in South America more than 10,000 years ago, and they were first enjoyed and used in food by local tribespeople. By 1500 BC the Incas were using them as sacrificial offerings and even included them in tombs.

When Spanish colonists arrived, local people were readily cultivating these incredible plants. Europeans knew they were special, and brought peanuts back home with them as gifts to their rulers and sponsors. In his 1609 Incan chronicle, Garcilaso de la Vega (1539–1616) documented locals toasting and eating peanuts and combining them with honey to make a kind of nougat. He also wrote of peanut oil being used to treat and cure numerous illnesses.

By the end of the 16th century, peanuts were on the move. Spanish explorers were carrying them to China and the Philippines, and the Portuguese brought them with them to West Africa. From there, they spread across the continent, and to India.Their introduction to North America in the 1700s and indeed much of their history throughout this later period was fuelled primarily by the transatlantic slave trade, and by the 1800s they appeared as a commercial crop across much of the fledgling US.

Initially, in Virginia, they were primarily planted by enslaved people as a foodstuff, or else to feed livestock and for their oil. During the American Civil War, however, things changed, with soldiers on both sides coming to rely on peanuts’ high protein content for sustenance. This was quickly followed by an expanding industry supported by the development of production, harvesting, and shelling equipment.

As the transatlantic slave trade began to shut down throughout the first half of the 19th century, the peanut again rose to prominence as a source of alternative revenue. With European demand for vegetable oil and soap rising, peanuts were seen as an ideal, low-cost crop – assuming free labour could still be secured.

In the US, wider consumption was spearheaded by the ex-slave and agricultural scientist George Washington Carver (c.1864–1943), who helped to popularise peanuts in the South and championed their use in crop rotations to address the nutrient depletion caused by cotton monoculture. In addition, Carver developed more than 300 uses for peanuts, from recipes to industrial products, and it was around this time that peanut butter was also first developed.

As the 20th century progressed, industrialisation helped address the rapid growth in demand for peanut oil, roasted and salted peanuts, peanut butter, and confectionery. The US government even got involved in the early 1900s, instituting agricultural support programs to promote important crop production, including peanuts.

From there, peanut consumption and propagation accelerated, leading us to where we are today.

Historical peanut trade alignments

Peanuts were first traded between peoples in South America and Mesoamerica during the 1500s. Thanks to the Incas and the Nahua people, peanuts made their way across the continent, and were already fairly widely cultivated by the time Europeans arrived.

Ray Hammons writes that a Peruvian peanut variety was first transported to the western Pacific, China, Java, and Madagascar. Moving from Peru to Mexico, they were regularly transported on the “Acapulco-Manila” galleon line between around 1565 and 1815.

During these early days, the Indonesians became accustomed to consuming peanuts as a staple food product, and they became a key part of local food culture. However, with domestic farming unable to match demand, trade routes developed to ensure supply from neighbouring producers, including Burma, India, and China. These trade connections remain ever-present today.

Once full-scale cultivated production got underway, peanuts fed into the transatlantic trade, operating largely on national lines or within empires: whether British, Spanish, Portuguese, or Chinese. These trade volumes increased rapidly: Gambian exports to Britain, for example, grew from 213 baskets in 1834 to 47 tons the following year and thousands of tons a year by the early 1840s. The expansion of Gambia's peanut trade in this period was therefore not merely a result of local entrepreneurship, but also British and French economic influence.

The need to move peanuts around the African continent and to other parts of the world drove the laying of railroads, and so transportation routes also became intricately connected to the supply and demand needs of the peanut business.

In other parts of the world, trade restrictions – and their removal – played a major part. A shipment of 722 kilograms to Marseille in 1840 was followed by a reduction in the tariff, leading to much larger shipments landing in Marseille by 1848 to fuel a growing domestic peanut oil industry.

The other big development was in consumption habits. Until the 1900s, peanuts were primarily consumed roasted in the shell, but efforts were made to popularise peanut butter consumption, with numerous brands available to the US market by 1899. By adding further processing needs to the supply chain, the domestic manufacturing industry developed rapidly, fuelling further demand from primary supply sources in major growing regions.

Globalisation: Trade route development in the last 30 years

Since the days of early industrialisation, trade routes have developed rapidly, driving the recent surge of globalisation. The worldwide peanut market is now vastly valuable, with exports hitting a total of US$4.03 billion in 2021.

First up, let’s look at the countries importing peanuts and peanut products in large quantities

It’s not uncommon for a small handful of origins to dominate even the most complex of markets’ trade routes. In the US for example, 44.6% of imported groundnuts come from Paraguay, 41.1% from Nicaragua, and 12.4% from Mexico (which represents the entire Mexican export stock). Nicaraguan and Mexican exports typically attract a far lower tariff

at the US border than competitors, in an effort to offset a dramatic reduction in trade value in recent years.

China imported 45.6% of its peanuts from Sudan in 2021, 34.8% from Senegal, and 11.6% from the US. European markets on the other hand tend to remain dominated by Argentinian imports: 55.8% of German imports originated there in 2021, 44.7% of French imports, 65.7% of the Netherlands’, and 37.2% of the UK’s imports.

In part, that’s due to a fortuitous seasonal match-up: European consumption is highest during the winter holiday season, and a trade bias that prioritises the final quarter of each year also suits Argentinian producers and the local growing climate.

As we’ve seen, the Indonesian market remains unsurprisingly dominated by high-producing neighbours. An incredible 80% of its 2021 imports came from India, and another 13.1% from China.

And what about the producers?

Geography and history remain key influencers. Indian exports tend to attract local consumers: 45.2% went to Indonesia, 14.8% to Vietnam, 9.4% to the Philippines, and 7.9% to Malaysia. Argentinian exports almost exclusively arrive in Europe, and the US primarily exports to Mexico (29.2%), Canada (23.9%), and China (19.1%).

Clearly, many trade routes remain entrenched along historic or geographical lines. An image of premium quality successfully projected by certain producers has drawn them closer to higher-value markets (such as Argentina has achieved in Europe), and others have been drawn to those who can supply a sufficient quantity.

Newcomers are also welcomed: Nicaragua is a rapidly developing peanut producer, having increased its exports of groundnuts from only around 100 tonnes in 2014 to almost 3,000 tonnes in 2018.

When an influential economic nation such as China for example dramatically ramps up its import needs, it is able to forge powerful new trade routes. African producers now tend to export almost exclusively to the Chinese market, reflecting a targeted campaign by China to obtain a larger supply of peanuts. For example, China attracts 96.5% of Sudanese exports and 92.4% of Senegal’s.

Finally, how about processed peanut products?

The peanut policy in the US was transformed in 2002 by the elimination of a decades-old peanut quota system that restricted the size of the local market. This allowed its booming peanut butter industry to continue to grow, although its export partners have continued to develop. As recently as 2017, Canada purchased 35% of US exports, another 19.6% went to the European Union, and a meagre 4% was traded with Mexico. By 2021, however, Mexican influence was on the up, with the country importing 50 million dollars’ worth of peanut butter.

The Netherlands, interestingly, exports almost half the total quantity of its peanut imports, primarily to Germany (48.2%) and France (19.3%). This is in part due to Rotterdam’s significance as Europe’s primary goods port, and its use for the re-export of goods to neighbouring countries.

Clearly, trade routes can continue to evolve significantly. One only needs to look at changes in the natural gas market during 2022 in response to the war in Ukraine to see how rapidly governments can adapt their trading systems given sufficient political will.

Conclusion: The future of the peanut trade

Geography and convenience – coupled with favourable regulatory conditions – will always be the biggest guide to changes in economic patterns and trading routes.

The connections and paths left to us by history remain influential, but new opportunities are emerging quickly which can be exploited by a wide range of stakeholders, thanks to just how well connected and accessible our world has become.

For example, as Chinese domestic consumption soars, and its exports drop (by 8% across 2017-21) whilst its imports accelerate dramatically (by 72% across 2017-21), there’s a significant opportunity for other origins and producers to fill the gap in the international groundnuts marketplace.

The future therefore lies in an interconnected global peanut ecosystem fuelled by market intelligence, crop expertise, and the generous sharing of knowledge. So that producers, manufacturers, and consumers can get the best possible deal, the highest quality, and the most appropriate specifications and origins of groundnuts to serve their needs.

To find out more about the future of the global peanut trade, and how Agrocrops industry expertise can unlock superior yields and deeper connections that deliver better results for everyone, get in touch.

With over 17 years of experience in the peanut industry and numerous awards recognising his contributions, he founded Agrocrops in 2008, a leading global peanut company. His passion for peanuts drives his commitment to improving the industry for all stakeholders and promoting sustainability.

Published on 18/11/2024 in

Published on 18/11/2024 in

Published on 15/11/2024 in

Published on 13/11/2024 in

Published on 03/16/2023

Published on 03/10/2023

Published on 03/06/2023

Published on 03/03/2023